Addressing Alcohol and Other Drugs

Drink driving is acknowledged by the international community to be one of the key road safety behavioural risk factors. Alcohol impairs many aspects of human functioning. As a result, drivers who have alcohol in their body have a much higher risk of crashing than drivers who have not consumed alcohol.

In most high-income countries about 20% of drivers killed in crashes have illegally high levels of alcohol in their blood, and in low and middle-income countries research has shown that between 30% and 70% of drivers killed consumed alcohol before the crash.

There is also a growing amount of research to show that certain other drugs (including cannabis, methamphetamine and ecstasy) and some prescription medications (benzodiazepines) also increase crash risk.

Much of the material below was drawn from Drinking and driving: a road safety manual for decision-makers and practitioners, which presents an excellent overview of the topic.

Alcohol

An effective strategy for reducing alcohol related crashes will include several components. The following actions have been found to help:

- setting blood alcohol content (BAC) limits

- educating the public about the dangers of driving after drinking

- informing the public about BAC limits and penalties for drink driving

- enforcing BAC limits

- restrictions on inexperienced drivers (for example, lower BAC limits for younger drivers)

- designated driver and ride service programs

- alcohol ignition interlocks.

To be effective these actions need to be widely publicised, and publicity needs to be ongoing. Publicity also needs to be targeted to key groups. The penalties (fines, loss of licence, mandated use of alcohol ignition interlocks) need to be large enough to act as a deterrent and the public need to believe that there is a high likelihood that they will be caught if they drink and drive. Using these measures will eventually change community attitudes to drink driving behaviour.

Setting and enforcing BAC limits

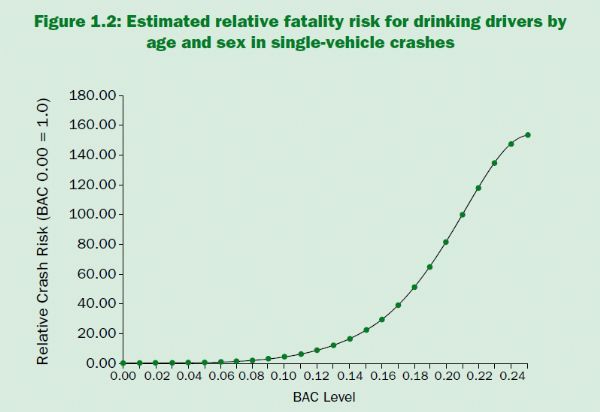

In general, a law which defines an upper legal BAC limit is required so that police can enforce anti-drink driving laws. Most countries have adopted a BAC limit of either 0.05 grams per 100 ml of blood (g/dl) or 0.08 g/dl. The Global Status Report on Road Safety identifies a limit of 0.05 g/dl for the general population and 0.02 g/dl for young and novice drivers as best practice. The link between BAC and crash risk is shown by the graph (see Related Images). The graph shows that at a BAC of 0.15 g/dl, a driver’s risk of crashing is over 20 times that of a driver who has a BAC of zero.

Having in place sufficient enforcement activities such as providing police with powers to stop and test motorists at the roadside, random breath testing or sobriety checkpoints, and compulsory testing of all drivers involved in a crash are useful actions to show drivers that they are likely to be caught if they disobey BAC laws. The Guide to the Use of Penalties to Improve Road Safety shows that appropriate penalties are also important in discouraging drink driving and in communicating the seriousness of the behaviour.

Designated driver and ride service programs

A designated driver agrees to remain sober so he or she can drive others home after an event. This is an effective programme for young people who often share a vehicle and can take it in turns to be the designated driver to ensure that one member of the group remains sober. Some proprietors offer designated drivers free non-alcoholic drinks. Ride service programs also provide transport for people who have consumed alcohol and may otherwise drive.

Alcohol ignition interlocks

An alcohol ignition interlock can be fitted to motorcycles, cars and trucks. A vehicle fitted with an alcohol ignition interlock will not start unless the driver passes a breath test for BAC. Alcohol ignition interlocks are used successfully in some developed countries to deter repeat offenders drinking and driving and are also being introduced for first time offenders in some jurisdictions.

Other drugs

Like alcohol, other drugs can slow reactions, distort perceptions of speed and distance, and reduce concentration and coordination. Drug driving can be addressed in a similar way to drink-driving. For example, in Australia police conduct random roadside tests of drivers and riders for drugs.

Costs and effectiveness

It is not possible to cost or assign an effectiveness rating to alcohol or drug driving prevention activities, as the costs and effectiveness will vary dramatically depending upon what activity is undertaken. However, an effective strategy has the potential to prevent a large proportion of road fatalities. As an example, drink driving checkpoints in Australia have resulted in a 13% reduction in crashes (Elvik et al).

Treatment Summary

Case Studies

Related Images

A breath alcohol test device used in police enforcement. Image credit: iStock

A breath alcohol test device used in police enforcement. Image credit: iStock Police random breath testing, Australia. Image Credit: Unknown

Police random breath testing, Australia. Image Credit: Unknown UN Road Safety Collaboration, Drinking and driving manual

UN Road Safety Collaboration, Drinking and driving manual